A century ago, the murder conviction of two Italian immigrants set off a worldwide protest movement and revealed a polarized America.

By Bruce Watson, July 9, 2021

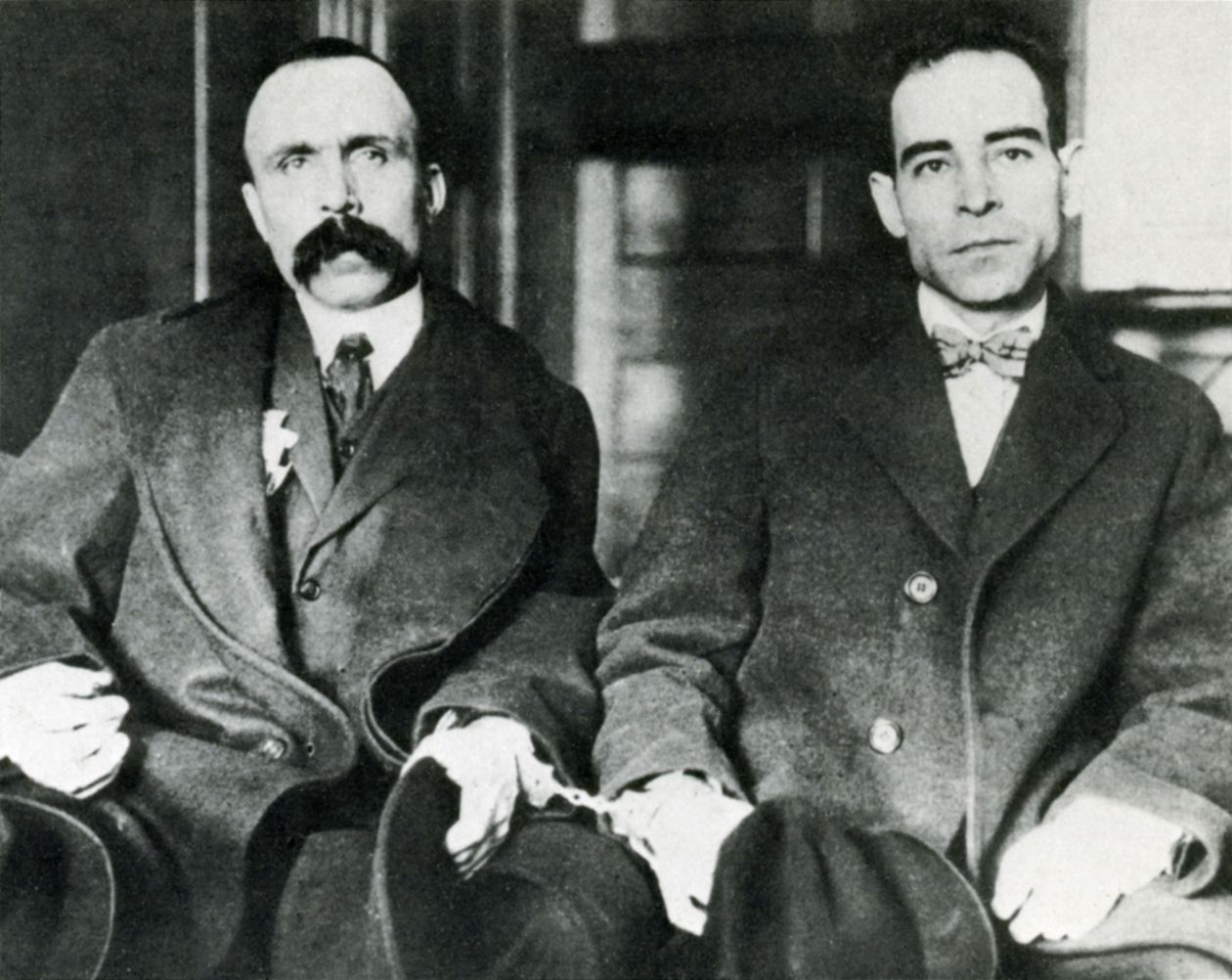

A century ago this week, on the evening of July 14, 1921, a verdict was announced in the murder trial of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The complex trial, held at the courthouse in Dedham, Mass., had lasted seven weeks and involved 167 witnesses, with confusing ballistics reports and testimony in Spanish and Italian. Deliberations were expected to drag on for a day or more, but just hours after closing arguments the jury pronounced the men guilty, and they were sentenced to death. Sacco, a 30-year-old shoemaker, cried out in Italian, “Sono innocente!” (“I am innocent!”). Vanzetti, a 33-year-old fishmonger, seemed stunned.

At the time, the conviction of Sacco and Vanzetti was barely noticed by the wider world. Within a few years, however, the case had become a political cause célèbre. Claiming the men had been convicted for their political beliefs, protests raged in capitals from London to Tokyo. A century later, the affair, with its dueling accounts of the facts and intense ideological passions, offers a reminder that political polarization in America has been with us for a long time. On the eve of Sacco and Vanzetti’s execution on Aug. 23, 1927, the novelist John Dos Passos wrote: “All right, we are two nations.”

The saga that ended in the electric chair began on April 15, 1920, when two guards were gunned down outside the Slater-Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Mass. Two gunmen escaped with the steel boxes containing the factory’s payroll, some $15,000. Under intense pressure to solve the shocking crime, the police staked out a mechanic’s shop where they believed a car connected to the robbery was being repaired, and a few weeks later Sacco and Vanzetti showed up to retrieve it, falling into the trap. At the time of their arrest they were armed to the teeth, and in mug shots published throughout Boston they appeared as sinister “yeggs,” the 1920s term for a gangster.