May Day isn’t just an estimably American holiday, it’s a particularly Rust Belt holiday, forged in the cauldron of Chicago’s streets and factories, born from the experience of workers in the mills and plants of Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland.

By Ed Simon, April 29, 2024

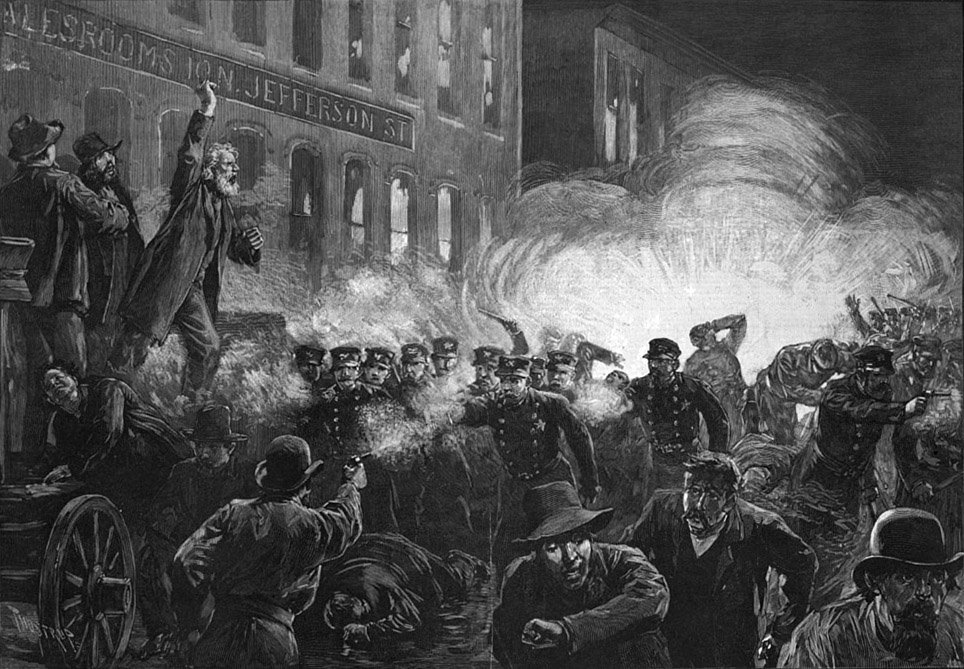

When forty-thousand workers marched down Chicago’s Michigan Avenue in 1886, their platform was the slogan “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, and eight hours for what you will,” coincidentally the same as the number of strikers who would be killed in the coming melee, half of them shot in Haymarket Square and the other half executed following a sham trial. A dead activist for each hour of the work day; a killed striker for each hour of nights’ sleep; a martyred worker for each hour of freedom. The Haymarket Protest, Affair, or Riot, depending on your political sympathies (historian Paul Avrich simply uses the word “tragedy”), was the culmination of decades-worth of organization from groups like the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor, as well as an assortment of far more radical socialist, communist, and anarchist groups, such as the International Working Peoples Association, which in Chicago’s dew particularly from the immigrant German and Bohemian communities. The first of May, which long had resonance as a celebration of spring in many of the countries of origin for immigrant labor, had been idealistically set two years before by vote of the Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions as the date by which an eight-hour work day would be standardized. Protests for that May 1st , followed by a general strike, were organized throughout the northeast and the Midwest; in Chicago, the former occurred peacefully, until at the conclusion of what would be the day’s first shift, the police fired into a group of fighting workers and scabs, murdering two of the former. “Anarchism does not mean bloodshed; it does not mean robbery, arson,” said August Spies, upholsterer and editor of the radical newspaper Arbeiter-Zeitung. “These monstrosities are, on the contrary, the characteristic features of capitalism.” This was the context of the subsequent protests three days later, when labor was acutely aware of the capital’s power as aided by its loyal soldiers across the class line.

Who was responsible that May 4th for the crude incendiary device – the bomb – was a matter of debate both then and now. The police, naturally, maintained that it was thrown by someone among the contingent of anarchists, and perhaps it was. The strikers, meanwhile, fingered the possibility of an agent provocateur, a Pinkerton or scab purposefully inflaming what was waiting to catch on fire. There was talk of a mysterious “man with a briefcase” who’d arrived in Chicago from out east, who was interested in learning much about the organizers, which perhaps gives some validity to that hypothesis. Adolph Fischer, executed a year later for supposedly causing the riot, assumed that the dynamite was detonated by “some excited workingman,” and maybe that’s the most possible, some enraged, anonymous worker pushed into pyrotechnics by witnessing his fellow strikers shot dead a few days before. That the police were perfectly willing, happy even, to shoot into a crowd advocating for what to us should sound distinctly reasonable should have been cause for some excitement. Regardless of who was responsible for the explosion, the results were incontrovertible: seven dead cops and four dead workers. Four more would be added to that later tally, when fifteen men were charged, eight were convicted, of which two were commuted to life in prison, one was commuted to fifteen years, and one committed suicide in his cell, with four hooded and taken to the gallows where they were hung after singing La Marseille – Fischer, Spiess, George Engel, and Albert Parsons.

That’s the other incontrovertible truth of the Haymarket Affair, that if these are the definite deaths from that day, then these four executed men were clearly innocent. Two of those upon the gallows had been far from Haymarket that day, speaking at other rallies; Parsons and Spies were preaching on the dais in view of thousands of witnesses when the bomb was thrown; one defendant was at home, playing cards. None of these alibis stopped the police from raiding the offices of Arbeiter-Zeitung, where they arrested even the typesetters. During the subsequent trial, the defense admitted that none of the accused was literally guilty of throwing, or necessarily even building, the explosive device. So shaky were the arguments that several of the anarchists voluntarily turned themselves over for arrest, assuming that the charges would be thrown out. Yet the sentiment among the middle classes was arrayed against the workers by a press more than happy to comply with the dictates of moneyed interests. To the Chicago Tribune, the charged and the movement which they represented were “arch counselors of riot, pillage, incendiarism and murder;” for The New York Times, the anarchists were “villainous teachers,” a rebellion of “Bohemian sausage makers.” Whether or not it was Spies’ hand that measured out gunpowder or Parson’s that connected trigger wires was irrelevant to the commentariat; according to them, the explosion had already happened when the first types were set at the Arbeiter-Zeitung. That this was a free speech issue more than a question of terrorism was obvious to many, even while the editors at The New York Times and The Atlantic clambered for revenge. The Illinois miscarriage of justice was condemned by luminaries as local as attorney Clarence Darrow and as far afield as the writers George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde. “The trial of the Chicago anarchists has been recognized as one of the most unjust in the annals of American jurisprudence,” Avrich wrote in The Haymarket Tragedy. Far from being guilty, the Haymarket Four were, rather, the scapegoats executed upon the desert altar of capital.