Counterpunch | December 2, 2022

The Zapatista revolution has survived in Chiapas, southern Mexico, since 1914, and that is a miracle. Zapatistas endured the assaults of government paramilitaries, the betrayals of Mexican presidents and crushing poverty. “They don’t care that we have nothing,” the Zapatistas said of Mexico’s elite at the start of their first uprising, “absolutely nothing, not even a roof over our heads, no land, no work, no healthcare, no food, no education, not the right to freely and democratically elect our political representatives nor independence from foreigners.”

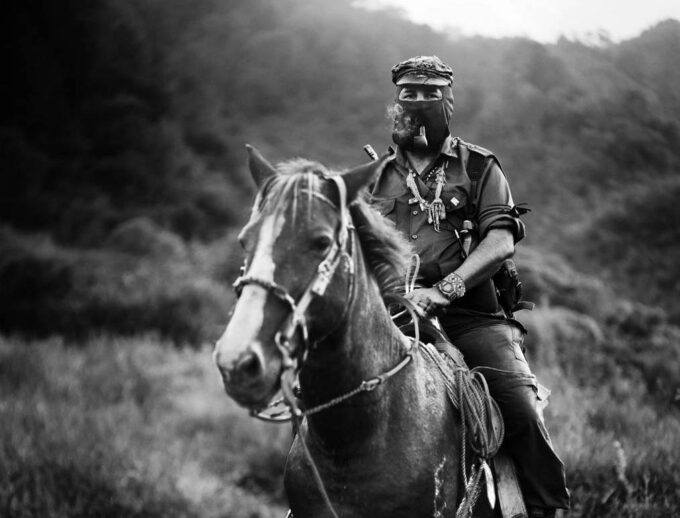

This specter of destitution loomed over the Zapatistas, and indeed millions of indigenous people because of NAFTA. After a 12-day war against the Mexican state in 1994, Zapatistas agreed to a ceasefire, maintaining control of their lands in Chiapas. Thus the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) is always ready for combat. Its soldiers may spend their days planting corn and beans, but at a moment’s notice they drop their hoes and grab their rifles. That’s because government paramilitaries could reappear at any time, and with them, the threat of reinstituting the near slavery of the abominable finca plantations. These fincas were the Zapatistas’ original target in 1994. The revolutionaries overran the fincas, expelled the owners and empowered the indigenous peons, thus ending the systematic rape of indigenous women and girls and the hanging of indigenous men who refused to hand over their daughters. The practice of whipping these serfs for the slightest infraction also stopped. In every way, life improved for these peons, who had previously been treated like dirt.

Women constitute a third of the Zapatista army, according to the introduction to a new book, Zapatista Stories for Dreaming An-Other World, by Subcomandante Marcos, their leader, if they could be said to have one. And women became pivotal to the Zapatista effort to create a new social-political-economic arrangement on their lands. “The proclamation of the Women’s Revolutionary Law before the 1994 uprising was an insistence that women’s rights cannot wait until after the revolution; they are part of the revolutions.” The Women’s Revolutionary Law included, for example, the right to drive; thus it enables women better to participate in what the Zapatistas accurately call “the neoliberal war against humanity.”