The Institute for Anarchist Studies, March 16, 2021

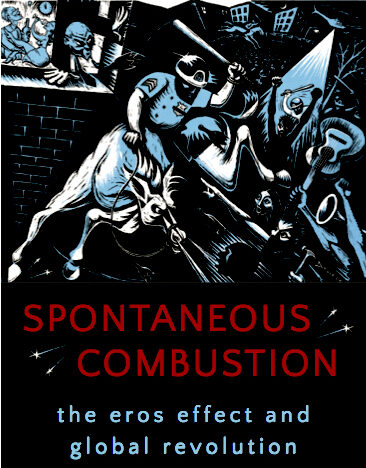

Jason Del Gandio and AK Thompson, eds. Spontaneous Combustion: The Eros Effect and Global Revolution (Albany: SUNY Press, 2017)

Hillary Lazar and Paul Messersmith-Glavin provide an introductory framing for this discussion here.

The publication of Spontaneous Combustion is a significant indication that popular uprisings are increasingly understood as vital to revolutions. Since the astonishing 1917 seizure of power in Russia by the Bolsheviks, the role of the “conscious element”—the Party—has been wildly overemphasized, while “spontaneity” was debased and ridiculed. Now that 20th century Soviet Communism is in the past, the time is long overdue to create social movements that can help to produce expanded freedoms, greater liberties, and joyful relationships—as well as to ruthlessly criticize tendencies within the movement that contribute to the deformation of freedom struggles and turn them into their opposite.

In the past century, while Leftists fetishized centralized organization, mainstream academia in the West, which had vilified social movements long before the Russian revolution, slowly moved toward rationalistic theories that prioritized resources in understanding a set of phenomena previously comprehended as seasonal fluctuations or short-circuiting electrical components of a smoothly functioning system. To make matters worse, copy-cat revolutionaries and tenure-seeking professors continually pour new wine into such old bottles, dutifully quoting fashionable theorists, often without bothering to have critically reviewed the practical implications of previously conceptualized frameworks.

The Eros effect was first uncovered in 1983. After five years of research on 1968, no academic theory could help me adequately understand what I was only beginning to comprehend as a world-historical wave of insurgencies. The global Sixties were neither a “moment in the movement of capital” nor the breakdown of a beneficent system. Since very similar movements simultaneously appeared in the Third World, the Second World controlled by the Soviet Union, and the economically developed countries, these popular revolts were not mainly products of similar national economic and political conditions. Nor were they produced predominantly by urbanization, migrations from countrysides to cities, concentrations of university students, age cohorts or generational conflicts—variables often employed to explain them.